A 10, 000-year-old process is gaining new attention thanks to the craft industry!

What am I talking about?

BEER! Yessss, beer.

Now that I have your attention, the fun can begin! Okay, but seriously…Beer is one of the oldest, and most widely consumed beverages in the world (Poelmans and Swinnen 2014). You may have heard that beer was a staple source of nutrition in Ancient Egyptian times, thousands of years ago, but did you know that it may date back to 8000 BCE (Legras et al. 2007)? Some research even speculates that grain was harvested for beer before it was for food in certain cultures (Poelmans and Swinnen 2014)!

Unfortunately, when you think of beer, you may think of drunken frat boys or Oktoberfest shenanigans, but beer’s influence is not to be underestimated. Its cultural importance and history are a force to be reckoned with. Brewing is an ancient practice, and has arguably even helped shape multiple civilizations, and life as we know it today (Meussdoerffer 2009; Curry 2017*). So what is this magical substance made of anyways?!

Traditionally:

Water: For obvious reasons, beer is made mostly of water, but water with different mineral components can also influence the beer’s character (Bokulich and Bamforth 2013).

Malt: Fermentable material; Starch source of barley, wheat, oats, rye, corn, rice or sorghum which largely impacts strength and flavour of beer (Bokulich and Bamforth 2013).

Hops: Flowers from the Humulus lupulus plant; for flavour, bitterness, and preservation (Meussdoerffer 2009).

And most importantly…

Yeast: This microorganism is the soul and sole-purpose beer is what it is. This amazing single-celled fungi is responsible for fermentation (Pires et al. 2014).

Fermentation is the process by which yeast metabolizes the sugars extracted from grains, creating carbon dioxide and alcohol (Pires et al. 2014). This process also creates hundreds of flavour-active compounds like esters and higher alcohols which lend themselves to aroma and flavor (Pires et al. 2014). Most modern fermentation methods of beer involve domesticated strains of yeast, and are entirely controlled processes (Meussdoerffer 2009). These include:

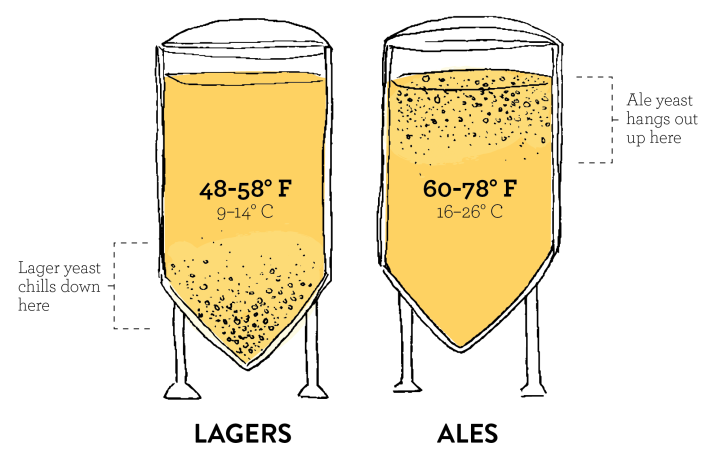

Bottom vs. Top fermentation. Used under public domain licensing.

Top Fermentation (named for the fermentation happening at the surface of the vat) by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: This is done at warmer temperatures, creating beers such as ales, stouts, porters, and wheat beers, and produces 5% of all beer worldwide (Varela 2016).

Bottom Fermentation (named for the fermentation being done at the bottom of the vat) by the yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus (an interspecies hybrid of S. cerevisiae and S. eubayanus): This is done at cooler temperatures, creating lagers and pilsners, and produces a whopping 90% of beer worldwide (Varela 2016).

However, one method of fermentation has an uncontrolled step, and that is the very special…

Spontaneous fermentation! This process is actually very old, and is how all beer used to be made, but nowadays only creates lambics, and new-age sour beers like American coolship ales (Carpenter 2017). These, as well as some other experimental types of beer, account for approximately 5% of all beer worldwide (Varela 2016).

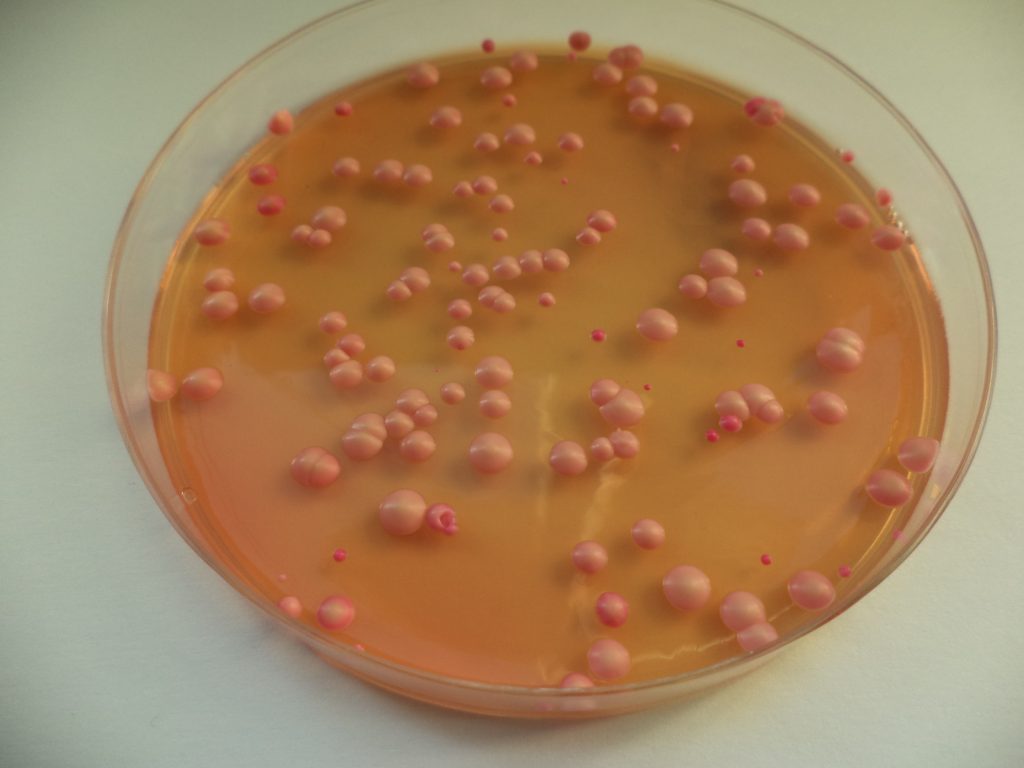

Brettanomyces (also known as “Brett”) is an Ascomycete (Spitaels et al. 2014) – with B. bruxellensis (teleomorph Dekkera bruxellensis) being the most commonly encountered species of these non-conventional yeasts (Crauwels et al. 2015) – and is the main microbe responsible for this spontaneous fermentation. In the brewing world, it is typically viewed as a contaminant, as the characteristics it imparts are considered unwelcome “off-flavours” (Carpenter 2017); however, in certain styles, particularly traditional Belgian ales like lambics, it is appreciated and encouraged (Crauwels et al. 2015).

Authentic lambics are the mother of all sour beers, and are only produced in the Senne River Valley region of Belgium near Brussels known as Pajottenland (Spitaels et al. 2014). These beers are unusual and unique for many reasons. Like beers brewed in ancient times, they are spontaneously fermented with wild, naturally occurring yeasts (and bacteria) (Spitaels et al. 2014) which reside in the air as well as in brewery equipment and entire structures such as decrepit roofs (Carpenter 2017). This makes every brewery’s lambic a different one, as unique microbes from that area are being introduced (Carpenter 2017). In fact, similar to France’s Champagne region, the fungi of Pajottenland are the only ones that can create an authentic lambic beer under Belgian law (Poelmans and Swinnen 2014).

Lambic brewing is an extensive process, with a lengthy fermentation period: After malting, and mixing, spent hops (old, dried flavourless hop cones that will impart preservative qualities, but not flavour) are added to the boiled wort (basically a hot, soupy grain and water mix). It is then exposed to the atmosphere overnight in an open, shallow vessel known as a “koelschip” to welcome these wild yeasts (Carpenter 2017). The duration of fermentation is 1–3 years in wood casks, which even have microbes of their own (Petruzzi et al. 2016). In fact, up to 120 different yeasts and bacteria have been found in the cooled wort, but the main yeast responsible is Brettanomyces. Brett produces several volatile compounds that are associated with the typical flavour of lambic beers, including ethyl phenol, ethyl guaiacol, isovaleric acid, acetic acid, and ethyl acetate (Basso et al. 2016). This results in many interesting flavour profiles, and peculiar sensory attributes including (but not limited to): “horse blanket”, “barnyard”, “acrid smoke”, “bandaid”, “faecal”, “old leather”, as well as musty, cheesy, cidery, fruity, tart, and acidic yeasts (Crauwels et al. 2015). This is all the wonderful work of the yeast!

These are risky and expensive beers to make though! A percentage of beer always gets dumped because it is undrinkable (Carpenter 2017). Brett can do unpredictable things, and sometimes it doesn’t ferment or interact with the other ingredients the way the brewers hope. Every batch (and every bottle for that matter) is different, since the last stage of fermentation in some cases is in the bottle itself, and because so much time is invested in each batch (Piatz 2004). In the case of gueuze, a mix of young and old lambics, further fermentation even occurs: A “young” lambic (usually one-year-old) is mixed with (an) “old” lambic(s) (Piatz 2004). The older yeast then feeds on the sugars of the young lambic, allowing the mature beer to further mature, and creating more CO2, alcohol and flavours (Piatz 2004)!

For this reason, few authentic lambic breweries remain, but in the past few years a sour beer renaissance has begun (Bubak 2016) *! Brewers from all over the world are taking inspiration from this Belgian sour and re-inventing it with exciting new flavours (Bubak 2016) *.

KRIEK (pseudo-lambic with cherries, brewed with B. bruxellensis) re-released this week by Driftwood Brewery, Victoria, BC. Used under public domain licensing.

Indeed, with the boom of the craft beer industry, especially in the past decade, spontaneous fermentation has been given new attention, and rightly so. Although this particular field has just begun to be explored, there is growing evidence of the enormous potential for the application of non-Saccharomyces yeast in the brewing industry (Krogerus et al. 2017). Funding opportunities, even in Canada, are being handed out to experiment with these special yeasts (Bubak 2016) *.

In conclusion, our history is being brought back to us through a rising interest in spontaneous fermentation, Brettanomyces yeasts, and these new sour beers, and a future is even being opened up! BUT! Although palates are being expanded, and people are becoming more adventurous, it may not be for everybody. The work of Brett and the creations of spontaneous fermentation are still very much an acquired taste.

*These articles are PRINT only. See references below.

References:

Bubak S. 2016. The craft of beer making. Portico 48(3): 24-27.

Curry A. 2017. A 9,000-Year Love Affair. National Geographic 231(2): 30-53.

Recent Comments