Introduction

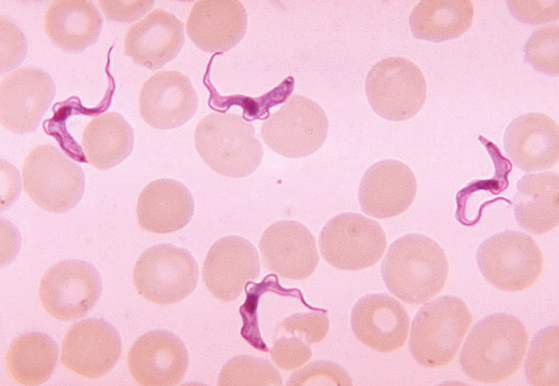

Throughout the world, there are many diseases transmitted to humans by an insect vector. Chagas disease, one of the most prevalent diseases in endemic areas of Latin America, caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. This disease is transmitted to humans through triatomine bugs or kissing bugs. The kissing bug is a hematophagous insect that feeds on the blood of its host. Once T. cruzi infects a kissing bug, the infected insect transmits the parasite to a mammalian host by defecation onto the open bite wounds. Once domestic animals are infected with the Chagas disease, the transmission to humans is very easily contracted. Chagas disease is a global issue impacting an estimated 6-7 million people and places 100 million at risk for infection. Due to the kissing bugs traditional habitat and behavior, Chagas disease is mostly associated with the poorest social strata’s. With the growing human population, the Chagas disease becomes a global public heath, political and social issue. The increased prevalence and transmission of this disease in society is described by the frequency and size of blood intake, the behavioral alterations and poor infrastructure conditions contributing to the global issue of Chagas disease.

Frequency and Size of Blood Intake

One of the main factors contributing to disease transmission is the frequency and size of blood intake from its host. There have been multiple studies suggesting the amount of ingested blood by the triatomines species having a positive correlation with their subsequent infection rate. Sex and the different developmental stages can influence meal sizes and therefore the disease transmission rate. Depending on the species of Triatomines, the nymphs can ingest up to 9 times their body weight when feeding. Females are also known to ingest larger amounts, approximately 2-3 times their body weight, in comparison to males who ingest much less. The differences in ingestion rates are important, as it shows the variability in the infection rate for the insect and the host. Uninfected kissing bugs in taking larger blood meal sizes have a higher probability of becoming diseased when it feeds on a host undergoing the chronic phase of the infection. The insect which, is now a carrier of the protozoan parasite, will continue the disease life cycle infecting other host species. Also, with the increased length of time an infected insect stays on a host, there becomes an increased possibility of disease transmission through its feces.

Behavioral adaptations

Infected bugs are known to have behavioral changes to increase the likelihood of disease transmission. Once infected with the parasite, the contaminated kissing bug will show an increased biting rate compared to an uninfected individual. This altered behavior can be the mere consequence of higher levels of starvation once infected with T.cruzi. The eagerness to bit can suggest an increased number of potential wounds for parasite contamination. In addition to the increased biting behavior, the temperature similarly impacts the disease transmission. In the warm summer months, there is an overall higher locomotion in vector mobility. Temperature differences also affect the home range size and host availability. With mammal hosts more abundant in summer, there is a higher probability of disease transmission during warmer months .

Host variability also influences the kissing bugs behavior and parasite transmission. The deforestation of the natural forests for agriculture and livestock had caused the kissing bugs to change its traditional habitats and food sources. Once the forests spatial distribution changed, the kissing bugs began to colonize areas surrounding human dwellings and feed on the available domestic animals. This particular adaptation to feeding primarily on domestic dogs, cats, birds, and rats have caused an increase in available human contact. Environments colonized by multiple vectors are more likely to have an apparent lack of host-specialization allowing the kissing bugs to expand their traditional niche and have a higher human transmission rate. Although there is no host selection due to the lack of major differences in nutritional blood quality, there is a difference in ingestion rate between hosts. The intake rate tends to be higher when bugs feed on avian hosts opposed to mammalian hosts. Since the ingestion rate influences the transmission rate, birds have a higher risk of infection. Birds also have greater habitat range so that they can transport infected bugs directly into human society and human infrastructure.

Society issues-Poor Infrastructure

The expansion of the human population has caused the kissing bugs to adapt to a new niche. The development of human society has also contributed to the transmission rate of this disease. As the kissing bugs are native to Latin American, the poverty and poor infrastructure contribute to the Chagas disease associating with the poorest social strata. The reduced quality infrastructure becomes the perfect niche for the infected kissing bugs. During the day, when humans are most active, the various crevices in the housing surfaces serves as a protected daily hiding place. At dusk when activity decreases, the bugs can venture throughout the house for food, infecting the sleeping humans.

Social, Health and Political Issues

Although it is well known for poor infrastructure to be the leading cause of transmission, inadequate health care, increased immigration and donation of organs or contaminated blood is also contributors . As the growth of legal and illegal immigration become a significant part of today’s society, infected individuals cause a major threat to the transmission of Chagas disease. In 2006, there were an estimated 529,360 infected immigrants from Latin American that immigrated to Canada. The political problem regarding migration control has affected social aspects since immigration is often necessary to provide labor and jobs to those in less developed countries. The imposed threat of disease transmission by immigration allows this disease to have a widespread political and ethical issue.

Another cause of parasite transmission is the use of blood transfusions and organ donations from individuals with the Chagas disease. Although the human immune response reduces the concentration of parasites in some tissues to end the acute phase of the disease, most of the protozoan resides in specific tissues indefinitely. This persistent infection also imposes a threat to women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, as vertical transmission between mother and fetus is known to occur. As the parasite in the blood stream is released periodically, the circulation of the parasite differs throughout time. While it is seen more uniform with high-intensity infections compared to lower intensity infections, individuals may not be showing signs or symptoms of infection before donation. This particular life history trait contributes to the global health and social issue when donating blood or organs.

With multiple aspects influencing human contact with the kissing bugs and the protozoan T.cruzi, the spread of Chagas disease imposes many options for prevention and management. Some operational ideas include improvement of housing conditions, spraying the pesticide cyfluthrin , screening individuals before immigration or blood donations, further research into new prevention drugs, continuous health education and community participation. The globalization of Chagas disease has become a global medical, political and social issue. Therefore, Chagas disease requires all stakeholders and health authorities to implement prevention and control measures to face the challenges that this infectious disease represents.

Recent Comments