After getting bit by a radioactive spider, Peter Parker gained superpowers- superhuman strength, enhanced senses, and the ability to climb walls- to become his alter-ego, Spiderman. I’m sure we are all familiar with the fictitious comic book plot, but maybe it’s not so far fetched. What if I told you that the bite of another arachnid also had the ability to change your internal body chemistry to transform you into another person?

Let’s look at a hypothetical situation. Imagine you are out for dinner with a group of friends you met on a hike the previous afternoon. You take a look at the menu, and something immediately catches your eye- a 12 oz top sirloin steak. You decide you’re going to treat yourself and place your order. After eating the tender, delicious steak and spending time with friends, you return home and promptly go to sleep. Suddenly, in the middle of the night you are awoken by the feeling as if your body is on fire. You think you might have a fever, and figure it’s just the common flu until you look at your skin and see you are broken out in hives that begin to itch severely. You try to wait it out to see if your symptoms go away, but they only worsen. Your airway now starts to constrict, making it difficult to breathe. You immediately call 911 and are rushed to the emergency room.

So how did a great dinner with friends end up with you taking a trip to the emergency room? The culprit is a small friend you encountered on your hike the day before. You were about to discover how much of an effect one small bite could have on your every day life.

The Culprit

Lone star tick sex-varied anatomy. Note the difference in colour, as well as the presence of a white star shape on the back of the female. Photo by CDC public domain, via Wikimedia commons (modified image).

The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) is an ectoparasite that is part of the order Ixodida. These ticks appear round and shape and have differential appearance based on sex. Adult female ticks are generally larger than males, and also appear reddish-brown in colour with a white star shaped design on their backs. Adult males, on the other hand, are smaller and darker in color, with the presence of a white pattern along the outer circumference of the lower body. This tick resides in temperate and tropical regions, and is primarily found in the southeastern and eastern United States. They thrive in meadows and wooded areas that are the result of secondary succession, as these are habitats where their required host, the white-tailed deer, resides. To complete its life cycle, the lone star tick requires a total of three hosts. While one of the hosts must be the deer, the other two hosts can vary between an array of large and small mammals. Some of the known hosts of the lone star tick are bovine, horses, goats, sheep, cats, dogs, birds, and humans.

The Mechanism of Vegetarianism

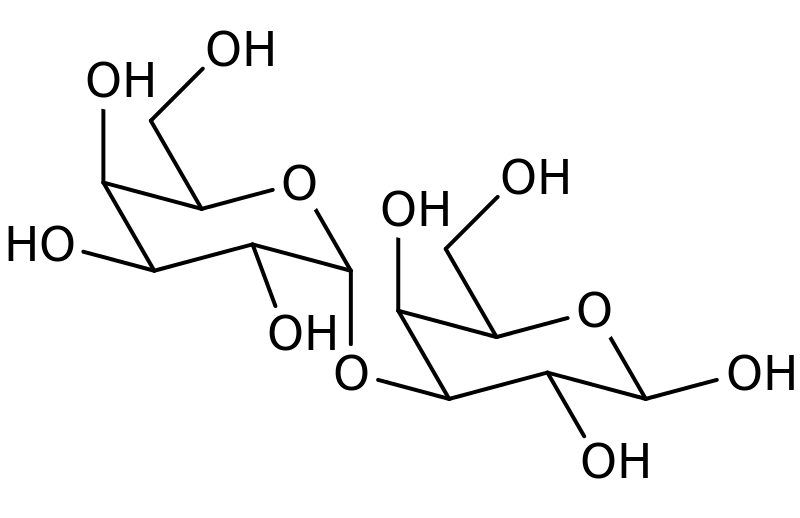

You may be wondering how the bite of such a small pest is able to elicit a delayed anaphylactic response in red-meat eaters. When a tick bites a human, proteins in the tick’s saliva are transmitted into the victim’s bloodstream. The body’s immune system recognizes the foreign particle and begins to create antibodies that will recognize the particle and eliminate it from the body. Unfortunately, an oligosaccharide, galactose-alpha-1,3- galactose, is present in red meat and induces the same immune response when introduced to the body through ingestion.

These results were observed in a study performed by Commins et al. The team of researchers performed serum assays in three subjects, screening for the presence of IgE antibodies to alpha-gal before and after being bit by the lone star tick. Of the three subjects, two had experienced an allergic response 3-4 hours after eating meat while the other did not experience such symptoms. Upon analysis of the serum assays, it was determined that the two who experienced anaphylactic symptoms had significant levels of alpha-gal specific IgE. In contrast, the subject who did not experience anaphylactic symptoms had only a 1% increase in the levels of alpha-gal IgE. This study provided strong evidence that the bite of a lone star tick induces the body to produce an antibody that targets both tick proteins and alpha-gal.

Besides causing these uncomfortable anaphylactic symptoms, lone star tick induced red meat allergy can have other negative impacts on the day-to-day lives of those bitten. This can include social life limitations such as going to eat at restaurants of having family barbeques. These activities prove to be difficult as there is a high risk for red-meat contamination when food is not carefully prepared. Unfortunately, the only way to guarantee no cross-contamination is to cook at home which hinders a lot of social gathering opportunities. The allergy can also translate to other red meat derived products such as dairy products and gelatin, seriously limiting the diet of those bitten. Additionally, this allergy poses medical concerns as many IVs contain gelatin. If a bitten individual required an emergency IV, they would not be able to receive one which could threaten their chances of survival in detrimental situations.

The Lone Star Tick as a Forest Pest

Besides affecting humans, the lone star tick also has negative impacts on other forest animals including its obligate host, the white-tailed deer. While the tick feeds on the deer during its reproductive stage, it transmits the bacteria, Ehrlichia chaffeensis to the deer through its saliva, causing ehrlichiosis. This bacteria compromises the immune system of the deer, making them more susceptible to opportunistic infections ultimately resulting in negative consequences on deer health and population. The consequences of the lone star tick’s actions as a forest pest extend to affect humans, who use deer for hunting purposes as a way of recreation.

The Silver Lining

Although this pest has many undesirable qualities, there is a silver lining. Due to recent studies, researchers have hypothesized that the lone star tick might act as a biological vaccine against Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Rash on a child’s hand due to Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Photo by Patho public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a detrimental disease that is caused by the tick-vectored bacterium, Rickettsia rickettsii. When first infected with this bacterium, humans experience symptoms such as sudden fever, severe headaches, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain within the first three days which eventually develop into more severe symptoms such as rashes, skin necrosis, gangrene, ulcers, and jaundice.

The lone star tick vectors a bacterium called Rickettsia amblyommii which is genetically similar to Rickettsia rickettsii. Rickettsia amblyommii, however, is not pathogenic in people. As such, researchers have proposed that exposure to Rickettsia amblyommii can give people immunity against Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Exposure to the non-pathogenic bacteria would build up an immune response, such that when it encounters the pathogenic form, it will know how to fight it off, thus not becoming ill.

This hypothesis was tested in dogs in a study in Oklahoma. The dogs were taken through woods that lone star ticks were known to inhabit. The dogs were monitored to see what bacteria they acquired from these woods and how their bodies responded. After the walk, it was observed that the dogs primarily acquired lone star ticks and analysis of their blood contents revealed the presence of antibodies against the Rocky Mountain spotted fever bacterium, however the dogs were physiologically healthy. Although these results have thus far only been seen in dogs, they could possibly be translatable to humans which sheds a positive light on the lone star tick.

So, although the bite of the lone star tick doesn’t confer superhuman abilities to its victims, there is no doubt that it has the possibility to change your life!

References

Bichell, R. E. (2015, October 28). The Lone Star Tick May Be Spreading a New Disease Across America. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots.

Carroll, L. (2016, April 20). Tick Bite Linked to Rise in Red Meat Allergies. Why Now? Retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/health/allergies/tick-bite-linked-rise-red-meat-allergies-why-now-n559346

Commins, S. P., James, H. R., Kelly, L. A., Pochan, S. L., Workman, L. J., Perzanowski, M. S., & Cooper, P. J. (2011). The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1, 3-galactose. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 127(5), 1286-1293.

Dantas-Torres, F. (2007). Rocky Mountain spotted fever. The Lancet infectious diseases, 7(11), 724-732.

Elliot, Lynette (2005, June 21). Species Amblyomma americanum- Lone Star Tick. Retrieved from http://bugguide.net/node/view/21258

Feder, H. M., Hoss, D. M., Zemel, L., Telford, S. R., Dias, F., & Wormser, G. P. (2011). Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) in the north: STARI following a tick bite in Long Island, New York. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 53(10), e142-e146.

Gladney, W. J., & Drummond, R. O. (1970). Mating behavior and reproduction of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 63(4), 1036-1039.

Lockhart, J. M., Davidson, W. R., Stallknecht, D. E., & Dawson, J. E. (1996). Site-specific geographic association between Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) infestations and Ehrlichia chaffeensis-reactive (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae) antibodies in white-tailed deer. Journal of medical entomology, 33(1), 153-158.

Smith, Gwen (2017). Red Meat Allergy: Incidence on Rise, Therapy in Works. Retrieved from http://c. http://allergicliving.com/2016/07/14/red-meat-allergy-incidence-on-the-rise-therapy-in-works/.

Sonenshine, D. E. (1991). Biology of ticks. New York: Oxford University Press.

Recent Comments