Periodical cicadas

Periodical cicadas are a mysterious group of insects (order Hemiptera) that like their name suggests, show up periodically, following either 13 or 17 year cycles. While there are around 3000 cicada species; only seven of them have periodical emergences: three 17 year species, and 4 13 year species, all of which are from the same genus, Magicicada. The species making up the 17 year cicadas include: M. septendecim, M. cassini, and, M septendecula, while the 13 year species are: M. tredecim, M. neotredecim, M. tredecassini, and M. tredecula.

Separated into broods depending on when and where they appear, the adult cicadas will mate and produce offspring, and subsequently die once they emerge – the juveniles of which will live underground for another 13 or 17 year period before they too emerge from the earth to repeat the cycle. However, this process of emergence is not perfect, and often times cicadas from broods will hatch early, or late, causing cicadas to show up when they’re not expected, or with broods they’re not associated with. These “stragglers,” tend to either be one year ahead or behind their own cycle, although there have been rare cases of up to 4 years. Since different broods are spread across North America, stragglers from one year don’t tend to join up with the current period cicadas (except where there is overlap), and the stragglers being lower in number tend to get wiped out by local predators so they are not reproductively successful. While broods are categorised solely on when and where they emerge, there is also differences in their distribution within North America; in addition, there have been evidence suggesting divergence in conspecifics from different broods in wing morphology.

Fun facts:

The last time it occurred was 1998, between the 13 year brood XIX and the 17 year brood IV.

Brood VI (When and Where)

Brood VI – a 17 year brood is schedule to emerge this year (2017), although you may encounter stragglers from Brood X

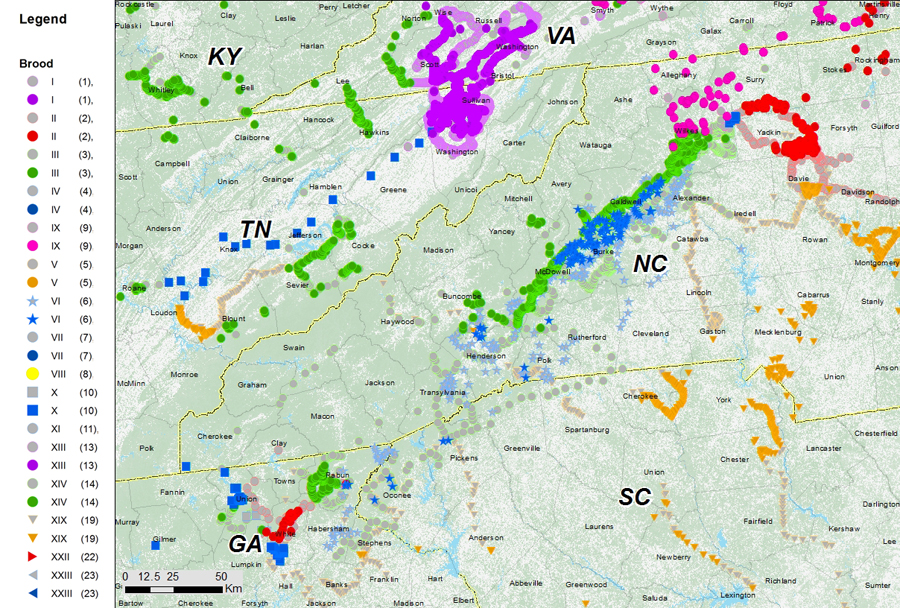

Periodical Cicada Brood Emergence Map. Taken from Cooley et al. 2011, used with Fair Dealings under Canadian Copyright Law.

If you’re looking to see Brood VI for yourself, make your way towards the east coast of America, in a small region around northern Georgia, western North Carolina, and northwestern South Carolina during early spring – they are expected late May and should be around for 6-8 weeks. If you want to catch the cicadas performing their harmonising choruses you should aim to get their within 2 weeks of emergence (although I’m sure locals will disagree with the sound) as the males will continue singing until enough of them die off such that the songs cannot be maintained. (Choruses start within 2-weeks and last less than a month.)

Impacts to vegetation

Although sometimes referred to as locusts, the swarming of periodical cicadas are not technically locusts, and they do not cause mass damage to crops. Adult cicadas don’t feed on plant parts such as leafs and barks like other insects (in fact, they don’t feed at all! All feeding is done during the nymph stage!), but they can cause damage to the trees the females inhabit when they dig groooves in to deposit their eggs. Generally any weak branches of trees can be damaged or killed off (called flagging) by the cicadas, however, there may be a benefit to the tree by pruning the weaker branches off.

The cicadas generally prefer deciduous trees to use as hosts so only the weakest/youngest trees are at risk of dying completely, while larger trees can get the benefit of pruning. Many fruit trees (like apple) are not native to North America and therefore have low tolerance for the cicadas* and are at risk of dying to them. This poses problems for farmers who likely have to take measures to ward off or kill the cicadas. In most cases though, the cicada needs the trees to survive and killing off their host would be detrimental to themselves. The general strategy for dealing with cicadas is to use a mesh-net to cover trees so that females cannot lay their eggs, or with the use of pesticides. Due to the short life-span of the cicadas once they have emerged as adults, as well as their poor flight capabilities; they generally are not a major contributor to plant pollination.

Human Impacts

Cicadas are not harmful to humans, in fact they possess almost no specialised defencive behaviours or body parts. They neither sting nor bite, and when approached they simply try to fly further away. They are not known to be poisonous or carry any sort of disease, and when handled all they do is defencively buzz… louder than usual.

While the old saying “they’re more scared of you than we’re scared of them” is probably very applicable for the cicadas; this doesn’t stop people from being afraid, panicked, or even disliking mass cicada emergences.

Generally localised to more southern and eastern North America, the people who live there have generally come to accept that every so often, these insects are bound to pop up in the billions. Those who have orchards or home gardens may be worried for their woody plants as that is the ideal location for female cicadas to plant eggs. People living in areas where periodical cicadas emerge are more likely to complain about the immense noise from the males trying to find a mate. Simply due to the mass numbers of the insects, they generally are louder than annual cicadas. Good news is that they are mostly active at day and unless you have the graveyard shift, it might not be a concern at all. Additionally, their chorusing generally lasts around a month’s time. The real problem may be for those with severe entomophobia, and having the sight of cicadas quite literally everywhere may induce panic attacks.

However, this doesn’t stop mainstream media outlets from other areas to capitalise on their emergence with flashy buzzwords/phrases such as “paralysis,” “how to survive”, “cicada invasion”, “outnumber people 600 to 1” and my personal favourite “swarmageddon,” to draw in new viewers to read their articles.

Cicadas as a Possible New Food Source?

Entomophagy, while a fairly novel idea to western society is one practiced by many cultures around the world for many years. There is recorded evidence of many Native American groups who have fed on the periodical cicadas and entomophagy is gaining traction. More and more people are willing to at least try insects as a high protein food. Even though the previously mentioned cicada ice cream was promptly shut down by health officials, the Missouri locals found great delight in the treat and it was a popular item despite only one batch being made. On the internet you can find various cookbooks, blogs, articles, and even snacks, for you to read/purchase if you’re interested in eating cicadas.

Entomophagy as a protein source is a huge interest of people, especially those concerned with environmental protection, and the consumption of cicadas and other insects may be a relatively easy way to solve their concerns.

Cicada Songs

Sure, the constant droning of the cicadas may be annoying, but some enterprising people such as David Rothenberg, has been going out into the fields while the cicadas are in bloom, and playing instruments in what he calls “an interspecies jam“. So even if you’re not into the whole insect eating business, there are many ways to interact and experience these amazing creatures.

Parting Thoughts

So if you’re not a complete entomophobe, maybe head down to the eastern parts of the United States this summer, and see for yourself the awesomeness of billions of cicadas everywhere. Even if you see annual cicadas every year, I’m willing to bet the amazing density of cicadas will blow your mind. If you’re even more adventurous, maybe try some of the many cicada recipes for your next house party. Whatever your interest may be, the cicadas are wonderfully mysterious and beautiful creatures that we should continue to learn about. So take a dive and get lost in the vast world of cicadas.

Learn about cicadas yourself! (Basic information to get started)

http://magicicada.org/magicicada/

http://www.livescience.com/57606-cicada-season.html

Other Resources Used

Cooley, J. R., G. Kritsky, M. D. Edwards, J. D. Zyla, D. C. Marshall, K. B. R. Hill, G. J. Bunker, M. L. Neckermann, and C. Simon. 2011. Periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.): The distribution of Broods XIV in 2008 and “XV” in 2009. The American Entomologist 57:144-151.

http://www.thekitchn.com/would-you-eat-chocolate-covere-148591

Marllatt, C.J. 2007. The Periodical Cicada. United States Bureau of Entomology Bulletin: 71. United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Entomology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Recent Comments